The modern concept of cryonics began to take shape in the early 1960s, at a time when rapid progress in medicine and technology started to challenge traditional definitions of death. The idea was simple yet radical: if biological deterioration could be stopped soon after the heart and lungs ceased to function, future science might be able to restore the individual to life and health once the original cause of death became treatable.

Early inspiration

The roots of cryonics trace back to early scientific curiosity about freezing and biological preservation. For centuries, experiments showed that certain small organisms could survive freezing temperatures, leading to speculation that more complex life forms might one day be preserved in a similar way. However, until the twentieth century, the idea remained theoretical.

The concept gained scientific credibility as researchers began to understand the role of temperature in slowing metabolism and biochemical reactions. In the 1940s and 1950s, advances in cryobiology demonstrated that cells, sperm, and small tissues could survive cooling and rewarming if treated with cryoprotectants, special compounds that prevent ice crystal damage. These early successes established the foundation for applying similar principles to whole organisms.

The birth of the cryonics movement

In 1962, a physics teacher named Robert Ettinger published a manuscript titled The Prospect of Immortality, in which he proposed that humans could be preserved at low temperatures after legal death and later revived using future medical technologies. The book captured public imagination and introduced the term “cryonics,” derived from the Greek kryos, meaning “cold.”

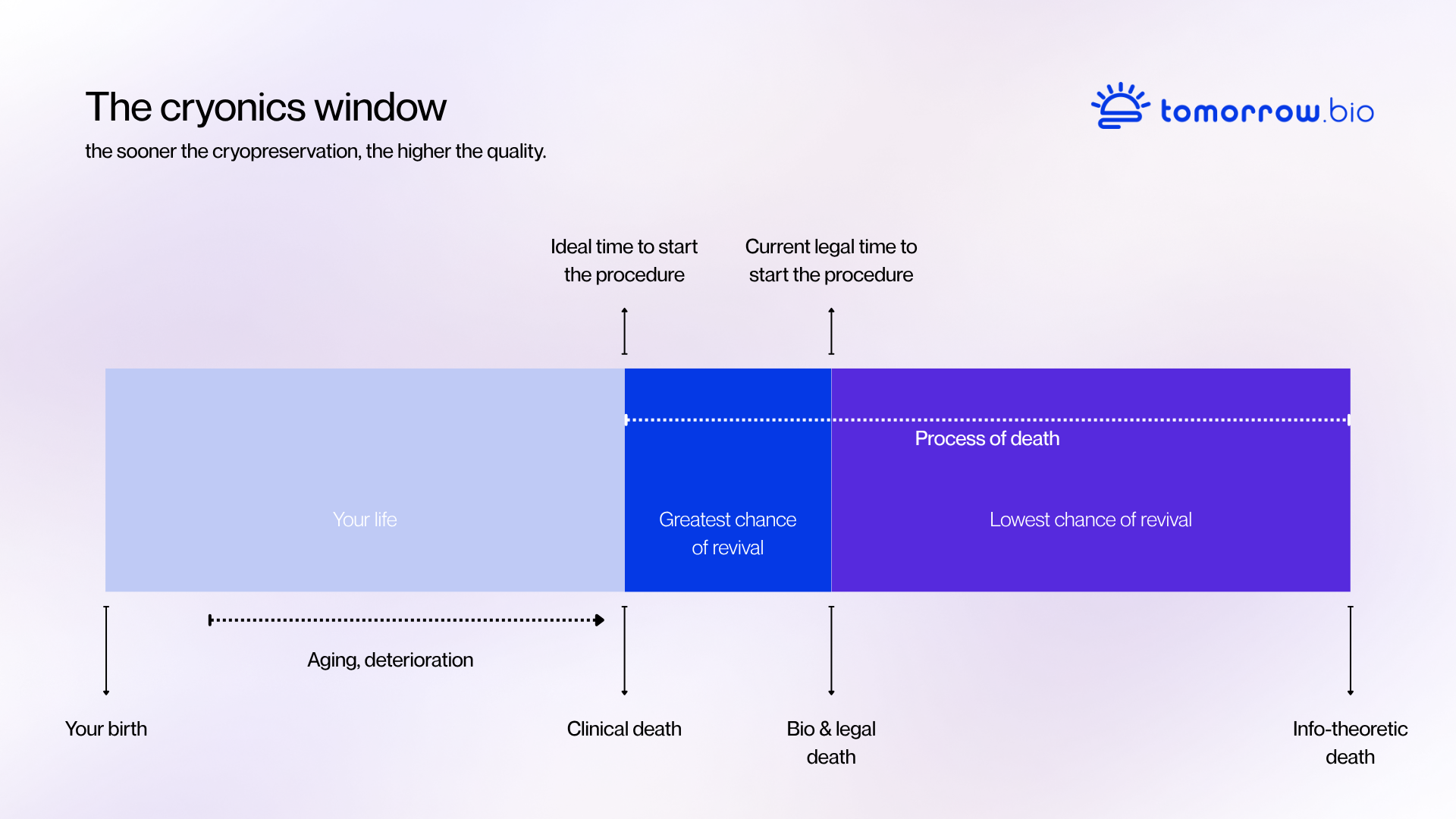

Ettinger’s argument was straightforward: if death is a process rather than a single moment, then preservation could be seen as an extension of emergency medicine. Instead of accepting death as final, one could maintain the body’s structure in a stable condition until new treatments or regenerative methods become available. This reasoning framed cryonics not as science fiction, but as a rational medical experiment extended through time.

By the mid-1960s, small groups of scientists and enthusiasts began forming organizations to put the theory into practice. The first human cryopreservation took place in 1967. Although the early procedures were technically limited compared to today’s standards, they established the essential structure of modern cryonics: immediate intervention after legal death, cooling, cryoprotectant perfusion, and long-term storage in liquid nitrogen.

Technical development and setbacks

During the 1970s and 1980s, cryonics moved from speculation toward more standardized procedures. Researchers refined perfusion systems, improved the chemical composition of cryoprotectants, and studied how ice formation damages tissues at the microscopic level. This period also revealed the importance of continuous maintenance and temperature stability in long-term storage.

Not all early preservation attempts were successful. In some cases, equipment failures or improper storage led to loss of preserved patients, which prompted the field to introduce stricter technical and ethical standards. These experiences shaped a more professional, research-oriented approach focused on reliability, transparency, and scientific improvement.

Vitrification and the cryonics of today

A major breakthrough came in the 1990s with the development of vitrification, a method that cools biological material into a glass-like solid without forming ice crystals. Vitrification made it possible to preserve cells, tissues, and entire organs with far less structural damage than conventional freezing. Applied to cryonics, it allowed for much higher preservation quality and became the modern standard for human cryopreservation.

Today, cryonics procedures rely on medical-grade perfusion systems, advanced monitoring, and optimized cryoprotectant solutions. The process begins immediately after legal death, with stabilization and cooling conducted by specialized standby teams. Once the patient reaches cryogenic temperatures, long-term storage takes place in insulated stainless-steel dewars filled with liquid nitrogen at -196 degrees celsius.

Research and the future

Cryonics continues to evolve alongside fields such as cryobiology, nanomedicine, and neuroscience. Research into tissue repair, cellular rewarming, and molecular restoration could one day bridge the gap between preservation and revival. At the same time, advancements in digital modeling and scanning are deepening our understanding of how memory and identity are physically encoded in the brain-knowledge that supports the fundamental premise of cryonics.

While revival remains a challenge for future generations, the scientific basis for preservation has grown stronger. Cryonics today is viewed not as a guarantee of future life but as an experimental medical procedure that extends the window of opportunity for recovery beyond the limits of current medicine.